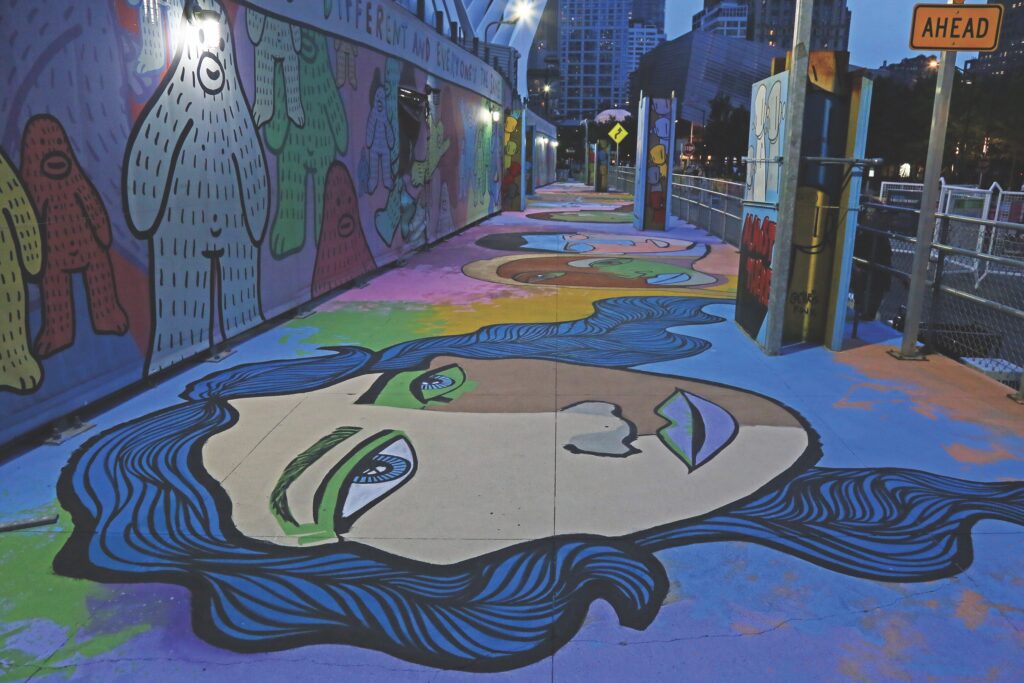

REAL LIFE PARTNERS AND STREET ARTISTS ALICE MIZRACHI AND JOEL BLENZ STAND BY THEIR NEW MURAL BY WORLD TRADE CENTER.

Photography by Joe Woolhead

Santiago Calatrava’s singular architectural ode to modernity, the iconic Oculus, stands beside a micro-hive of street art at the World Trade Center. I am meeting Alice Mizrachi and Joel Blenz (he is also known in the street art community as IF Trap), a couple bonded by their shared experience growing up in Queens and their craft: street art. The duo have recently completed a commission for Silverstein Properties entitled Faces of Our Community. The conical hiss of spray paint flows through the air as they sign their names upon the concrete canvas: a jubilant ‘smatter’ of colorful faces imbued with love and a sense of belonging peer out from beneath my feet. “I love the vibrant colors, the embrace of happiness, at the site of tragedy,” a passing tourist muses. I recently sat down with Joel Blenz and Alice Mizrachi to discuss their latest creation.

DOWNTOWN MAGAZINE: I read a quote attributed to actress Juliette Binoche, “In order to create, the need to express has to be bigger than the fear.” How does this sentiment relate to your life and career as a street artist?

ALICE MIZRACHI: One of the things Joel and I have commented often about is, that once they were arresting us because it was illegal, and now they’re paying us checks to do the same kind of thing. Maybe it’s not the same exact thing, but it stems from, or derives from, a culture that was born from kids wanting to express themselves because they didn’t have a voice in the city.

JOEL BLENZ: It’s a story of hiphop, and people expressing themselves, not only through art, [but] through dance, through rhyme, DJs. It’s come up through other ways, but it’s people competing non-violently to outdo each other. I’m going to make a better art piece than you. I’m going to do a better break dance move than you. I’m going to do a better rhyme than you, or disrespect you in a rap battle, non-violently. So that’s where it stems from. Like she said, now it’s a little bit more acceptable that people can do this.

AM:The graffiti of that time kind of evolved to this street art muralism, public art form that now is at a very high level in the art game and in the art market, in art history. It will be on the timeline of a movement that was critically documented and noted to be an evolution of the art form, and for meant for Joel, that’s extremely important, because we were there in its infancy, and we’re here now. We’re still doing it, you know, decades later, and having a commission like [this] with Silverstein Properties, and having Larry Silverstein hire us for this, it’s come true, because again, once we were being arrested, now we’re being celebrated.

DTM: What makes street art so powerful?

AM: The one thing I love about making art in public space, and the reason I became a public artist, besides the fact that it being a cool art form [was] developed by kids and made for the people. You know, everyone has access to this.This is not private. You don’t have to be wealthy to enter a gallery and museum. You don’t have to even care about art. It’s here. It’s for everybody to enjoy. It’s for the people, and it’s by the people. And for me, that was a really important part of art making because, a lot of people can’t afford art, right? Some people can. But what is the top 5% that could actually afford artwork in their homes? Making art on the streets or in public spaces kind of delineates that value. It just creates value for everybody. So it’s like the immigrant mom who’s walking home with groceries to go feed her kids at night to make dinner, doesn’t have to make this special trip to a museum. Also, to make art and to know that it’s not going to be forever, there’s sort of this freedom that it gives you, like, I’m making this now. I really don’t care what happens to it after, I’m done right now.

JB: It’s like what they do inTibet, they create it and they blow it all away. [A reference to a Tibetan Buddhist Sand Mandala].

DTM: What is the meaning behind your graffiti name ‘IFTrap’ and how does it relate to Joel Blenz?

JB: I’m from Jamaica, Queens. From a multi-religion, biracial family. So being a really young kid, not really knowing who I was, I felt stuck. I kind of felt like not a ‘pure breed’, if you will. So I felt trapped. So that was a name that really resonated with me. There are other people who go by “Trap,” so what we try to do in the graffiti circles is put a number or something after that, to distinguish you from the other person. So, specifically, I am IF Trap. IF is my crew, they’re the guys who I came up with in Queens. As I got older, I developed other things that moved me into the way of positivity. Like my Project Days of the Week. I used to work in banking, and every day I’d go to work, they’d be like, ‘manic Monday, terrible Tuesday.’ So finally, I was like, this sucks. I feel like my whole day is screwed just from hearing that in the morning. Let me come up with a project where it’s, ‘magnificent Monday, terrific Tuesday,’ all the way to ‘supreme Sunday.’ And now I have a days of the week project called “Everyday is a Great Day”, where I paint large murals with a positive affirmation in a neighborhood that really needs to see it. Joel Blenz is more of an abstract expressionist artist. Honestly, we were a bunch of broke kids in the hood, and all my friends would take spray paint, and there would be a little bit at the end of it, and they would throw it away. I was like, ‘Give me that, yeah, I’ll throw that on my next one.’ So I would just take 100 colors from ash cans and blend them together. And then finally, I came up with a blending style, because you can’t really blend with a skinny cap. When we came up doing spray paint, there was only a skinny cap, which means the paint came out in a really stark, sharp shot. As graffiti evolved, they became a fat cap which came out wide. So Instead of a straight shot, I can just take these two colors and almost create a third color from the blends that they’re creating, because of this cap. Hence Joel Blenz. It was just me being cheap and being creative and just finding a way to mix a style into the technology we had at that time.

DTM: What I admire most about this collaboration is the emphasis that is placed on highlighting community. Can you talk about what community means to you as an artist?

AM: I’ve often discussed it being sort of like we’re ‘the architects of communities’, and of our neighborhoods, with what we look at. And so in New York, you see a lot of advertisements, and it’s this corporate money behind that. It’s not something we can compete with, but we can go into our neighborhoods, and we can infiltrate from the inside.We can actually have an impact in a way that these corporations might try todo, but really can never do, because they’re not on the ground. So we look at it as like, Okay, we just built the architecture of this community right here. Whether it’s with the Rockwell Museum or the Smithsonian, we’re building the art, and the landscape that people are gonna walk by, and look at every day and be inspired by it. When you walk by a wall and you see art on it, it informs you, it impacts you. And not only when you walk by and see it, but when you participate in the making of it, now, you also own a stake int that neighborhood and in that property, and that’s why we get hired all the time. Because a lot of developers and a lot of real estate owners, they want the community to feel like they have a stake in what they’re developing. They want to be accepted and supported. So, when we do get hired, we ask a ton of questions to make sure that we’re not part of the gentrification. We want to make sure we’re actually part of uplifting the people who are already living there and supporting the locals who have been there for years.

DTM: As lifelong New Yorkers, what does painting at the site of 9/11 signify for you?

JB:So I was in the military, then became an electrician, then did 16 years in the banking industry, and I worked here at the WTC during 9/11. I was working for DLJ at the time, and was laid off two months prior to 9/11, but got rehired at Deutsche Bank two blocks down. So thank God I was laid off, because I was on floor seven at DLJ.

AM:I was working here as well at the same time too, without knowing him. Got laid off two months before the towers fell. So grateful I got laid off, because I survived.

DTM: The Universe works in mysterious ways.