Walking the line between risk and stability, telling history and imagining the future, art historian Johanna Burton embraces her role as MOCA’s first woman director. Photo by Alex Welsh

From DOWNTOWN’s Fall 2022 issue

JUST ABOUT TO COMPLETE HER FIRST YEAR as the Maurice Marciano Director of Tthe Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in downtown Los Angeles, Johanna Burton is MOCA’s first woman Director*.

Yet by her own assessment, she has been drawn to the museum for decades, and finds it a natural home. “Everything MOCA represents as a museum, I’ve admired my entire life,” says Burton, noting that MOCA not only has one of the most respected postwar collections in the world, but also a remarkable relationship with artists internationally and in Los Angeles. “I’ve seen a lot of MOCA shows over the years, including our Minimalism show, ‘WACK! (Art and the Feminist Revolution),’ and Murakami. I studied historical shows at the museum as a student, like curator Paul Schimmel’s ‘Helter Skelter,’ which just marked its 30th anniversary. Simply put, MOCA is incredible: Risky, edgy, kind of down and dirty…globally plugged in, while really caring about and reflecting its city. The museum attracts people like me to LA.”

Burton’s sense of having a deep relationship with a major museum on the West Coast may also have to do with Burton’s own background. She was previously the Director of the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, OH; the Keith Haring Director and Curator of Education and Public Engagement at The New Museum in New York; and the Director of the Graduate Program at Bard’s Center for Curatorial Studies (CCS) in upstate New York. In the late 1990s, Burton moved to Gotham to attend graduate school, with her time around the metropolitan area including studies for an M.A. in Art History, Criticism, and Theory from the State University of New York, Stony Brook; an M. Phil from New York University in Performance Studies; and an M.A. in Art History from Princeton University (Ph.D, ABD); as well as multiple turns at the storied Whitney Independent Study Program (ISP) as both participant and administrator. But first, Burton grew up in Reno, Nevada–“a pretty far cry from the New York art world,” she laughs—and attended the University of Nevada, Reno, as the school’s very first art history major.

“I always knew I wanted to be engaged with narratives of art and its place in society,” Burton says. “I wanted to spend time with living artists. And that led me into curatorial practice. Supporting artists is the most exciting part of my job today.” As Burton puts it, she remains especially inspired by artists who dare to explore “how power can be shifted through art”–artists who range historically and geographically from Sacramento, CA writer Joan Didion, who wrote about the Hollywood counterculture, repo to appropriation artist Sherrie Levine, and painter Kara Walker, whose works focus on race, gender, sexuality, and violence.

When Burton initially signed on to join MOCA last year, the previous director, Klaus Bisenbach–a high-profile name in the museum world (once Chief Curator at Large at the Museum of Modern Art, and a former director at MoMA PS1)–was to remain in a complementary capacity as artistic director. Burton took the full position as director when Biesenbach departed for the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin two weeks after the dual appointment was announced. “Every one of my predecessors brought a lot to the table,” continues Burton, acknowledging the institution’s past while looking enthusiastically toward its future. “I’m highly collaborative, and love building teams. I live, breathe, and work MOCA, but I really want to think outside of just a single perspective. I just hired a chief curator, Clara Kim, from The Tate in London–she will be a major thought partner for me, among others. Our exhibition program needs to tell a story; it should never be based on my own or any other individual’s taste, but instead should represent what’s groundbreaking in culture and singular for the institution.”

And that institution has a large footprint, allowing for many exhibitions to take place at once. In fact, MOCA has two primary spaces: MOCA Grand Avenue, which is, Burton says, “a 25,000 square feet, ironically now classic, post-modernist building erected in 1986 by the iconic Japanese architect Arata Isozaki.” This past September, the show Henry Taylor: B Side, opened at MOCA Grand Ave, spanning some 30 years of the artist’s work, representing Taylor’s first large-scale museum exhibition in his hometown.

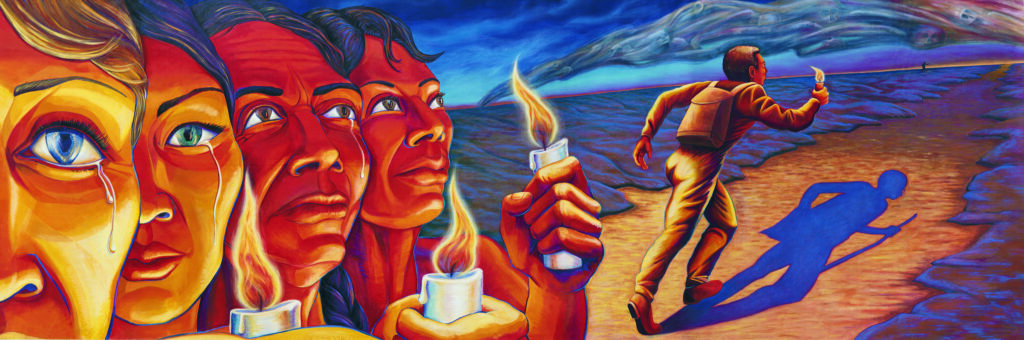

And then there is The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA in LA’s Little Tokyo historic district: “a former police warehouse that’s massive, a nearly 50,000 square foot experimental exhibition space,” says Burton. The Geffen was repurposed for this use by noted California architect Frank Gehry and has held countless now-historic shows of contemporary art. Currently showing there is Tala Madani: Biscuits, the first North American survey of the Iranian-born artist’s paintings and animations. “She thinks about satire, political humor, in global terms,” Burton notes, in a manner reminiscent of her admiration for Levine and Walker. “It’s funny, raw, nasty, in a good and super smart way.” Also on display is work by L.A. native Judith F. Baca. World Wall, a multi-panel mural Baca collaborated on with other artists during her travels between 1987-2014. “She’s an icon in LA, a muralist whose efforts on multiple fronts goes back 50 years,” Burton says. “I took a walk with her when she first arrived, I was just so incredibly inspired.” Alongside both of these shows is a third, ‘Garrett Bradley: American Rhapsody’; which is the first museum exhibition for the New Orleans born/LA based artist/filmmaker. “Garrett is a rising star; her work is both deeply affective and rigorous,” Burton says, enthusiastically.

Beyond such shows, Burton adds, “we have an incredible performance program,” in a dedicated 15,000 square space, Wonmi’s WAREHOUSE at The Geffen. MOCA recently brought aboard Alex Sloane as their Associate Curator, who largely oversees live art at the museum. This new (but also old–the museum has always been multidisciplinary) commitment to performance, bringing people together in spaces, is important, yet shows how, given how the pandemic is not over, MOCA is still taking precautions–and emphasizes its mission in a particular light. “This past summer, MOCA was back to five days a week, now six in the fall. We want to be really safe, still wearing masks, keep staff feeling motivated about bringing people together; live art occupies a funny space in the world. It can be a challenge, there was uncertainty there for a while. But artists are more relevant than ever, and coming together feels even more urgent and meaningful.”

This sense of a historical moment is amplified given how MOCA will be turning 50 In just seven years: ”a mature contemporary museum,” says Burton, who has on her mind “how to refine and re-articulate the Museum’s mission.” Today, she thinks about its “history, goals, exhibitions that people can access, technology that we should be putting our arms around, our digital archive, expanding offerings online. We are thinking about both history and the future, stability and risk, and the backward and forward sense of our returning to an institutional DNA that has always been experimental, while geared toward and open to new chapters. We want to set and meet challenges that are as exciting and innovative on the inside as on the outside. To be truly breathtaking and experimental, while building stability and sustainability. I’m excited about looking at both sides of that coin. And we know others are excited, too. The community really wants their MOCA to succeed.” DT

Judith F. Baca: World Wall; Garrett Bradley: American Rhapsody; and Tala Madani: Biscuits run at MOCA Geffen September 10–Feb. 19, 2023. Henry Taylor: B Side is on view November 6– April 30, 2023. For more information on MOCA, visit moca.org.

*MOCA Board of Trustees Chair Maria Seferian stepped in as Interim Director in 2013.