Evening Star, by Georgia O’Keeffe.

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time is an exhibition on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) that delves into the philosophical inspiration behind the artistic process of the Wisconsin born artist. O’Keeffe (1887-1986), a prolific artist colloquially known as the mother of American Modernism, sought to capture rhythm and essence over form in her works, which is evident in the fluidity and motion imbued in her art.

“To see takes time—like to have a friend takes time,” said O’Keeffe. She believed that, only in creating multipart drawings and paintings of the same subject, developing them throughout a sequence, would one truly be able to ‘see’ – to fully understand the nuances of one’s subject. O’Keeffe’s repetitive and persistent process allowed her works to grow from a single piece into a vivacious entity. She breathed life and dimension into her art by rendering, for example, a single flower in several different mediums, or by gradually stripping down an elaborate landscape and simplifying it to its essence. In doing so, she developed a striking voice and established herself as a pioneer of modern art, following her belief that artists should strive to express their personal experiences and viewpoints, rather than conform to established artistic norms. Devoted to this philosophy, O’Keeffe distilled her subjects to their essential elements, aiming to uncover their underlying spirit or energy.

The final piece in each series seems to be the one O’Keeffe most identifies with, but in including all variations as one cohesive work of art, one can go through the process of “seeing” along with O’Keeffe. Her open acceptance of imperfection, change, and inconclusively instills her works with a doctrine of multiplicity and transience. In her display of the process of fully capturing the subject, she postulates that a single picture cannot completely encapsulate the complexity of the subject. Whether it is a person, a landscape, or an object, it takes time to entirely capture a subject, and only once it is fully captured can it be understood and seen.

Between 1915 and 1918, O’Keeffe underwent an innovative period of experimentation. During those three years, O’Keeffe produced as many artworks on paper as she would over the subsequent forty years. These works included “progressions of bold lines, organic landscapes, and frank nudes, as well as the radically abstract charcoals she called ‘specials.’” Over the years, O’Keeffe gradually turned to painting as a medium, but several of her most notable and prominent series (flowers in the 1930s, portraits in the 1940s, and aerial perspectives in the 1950s) maintained her devotion to drawing on paper.

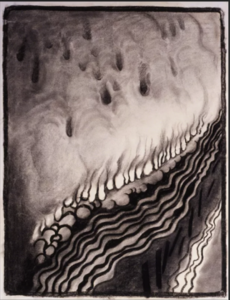

Many of O’Keeffe’s works are abstract, and she focuses more on capturing the feeling and essence of the subject in the motion of her rendition than on capturing exact form. One of her abstract drawings, a special entitled “Special No. 9,” made in 1915, is a charcoal drawing of a headache. O’Keeffe used charcoal frequently, believing that the medium had a particular “capacity for conveying a physical sensation.” Rather than drawing what it looks like to experience a headache, O’Keeffe sought to capture the feeling of the headache itself, creating a perhaps even more profound and intense work of art in abstraction, rather than attempting to capture it in its realistic physical form.

“Special No. 9,” Georgia O’Keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time showcases not only a body of artwork, but a meditative and powerful artistic worldview. The exhibit’s evocative display encourages visitors to embrace complexity and intricacy, and to slow down to take the time to understand. On now through August 12. moma.org.